Perspectives October 15, 2015

Calling for Progress: Racial Inequality and Criminal Justice Reform

Disparities in the criminal justice system remain a major obstacle to racial equality in America. While the problem goes beyond the laws themselves, legislative reform is a key component of any solution.

By Andrew Oravecz, Executive Assistant

Disparities in the criminal justice system remain a major obstacle to racial equality in America. While the problem goes beyond the laws themselves, legislative reform is a key component of any solution.

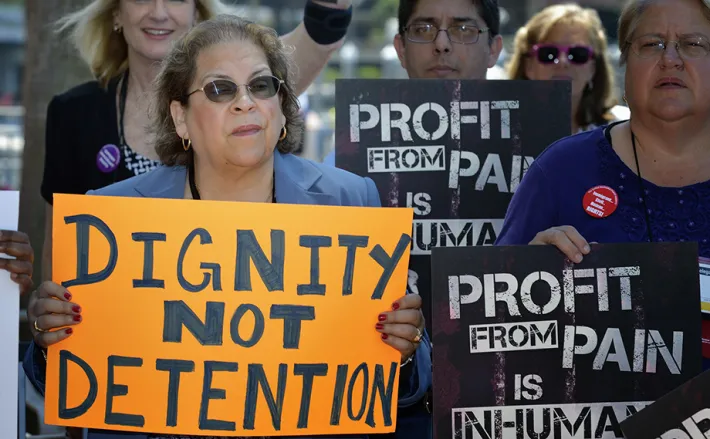

Photo Credit: UMWomen (Flickr/Creative Commons)

In spite of signature 1960s legislation intended to eradicate systemic racism from the political, social, and economic spheres, there are still structures in place that perpetuate unjust treatment and inequality within our society. One of the best examples can be found in the criminal justice system.

The United States incarcerates more people than any other country, and proportionally speaking, African Americans have shouldered much of this burden. Based on the 2010 census, 40 percent of all people behind bars in the United States were African American, even though African Americans constituted only 13 percent of the population.

Drug-related offenses play a role in these numbers. Despite similar rates of drug usage across all ethnicities, African Americans nationally are 3.7 times more likely to be arrested for offenses involving marijuana possession. Exacerbating the problem, laws that increase penalties for possession in school zones disproportionally affect poor, urban African American communities. A recent Wall Street Journal article illustrated this point by comparing maps of school locations in suburban Greenwich, Connecticut, and urban Bridgeport, Connecticut. The maps show that unlike in Greenwich, it is nearly impossible to avoid being near a school if you live in Bridgeport. The city’s population is 34 percent African American, while Greenwich is home to fewer than 1,000 African Americans, or about 4 percent of the total population.

States with expansive school-zone boundaries should take these facts into consideration when addressing reform efforts. Delaware, Massachusetts, Vermont, Minnesota, and a number of other states have succeeded in narrowing the radius of school zones to less than 1,000 feet, a reasonable goal for all jurisdictions.

Other legal reforms should address de facto racial disparities that stem from the way various drugs are handled. Large differences in sentencing guidelines for crack (used more often in poor, urban communities) versus powder cocaine (a more expensive product) have been well documented in the past. The federal Fair Sentencing Act, passed in 2010, brought the sentencing ratio between crack and powder cocaine down from 100:1 to 18:1, but further action still needs to be taken.

The proposed Smarter Sentencing Act of 2015 (S.502/H.R.920), introduced by a bipartisan group of lawmakers including Senators Mike Lee and Dick Durbin and Representatives Raul Labrador and Bobby Scott, would have a multitude of beneficial impacts on the criminal justice system. First, it would allow the Fair Sentencing Act to be applied retroactively, making thousands of convicts eligible for sentencing reviews. In addition, the bill would restrict the use of mandatory-minimum sentencing rules that require lengthy prison terms regardless of the circumstances in a given case. Though this bill enjoys broad support ranging from fiscal conservatives to staunch liberals, its proponents face an uphill battle. Most of those opposing the measure are conservatives of the “tough on crime” school. Members of Congress and others who favor fundamental fairness should be putting their weight behind this bill, while also noting the secondary benefit of reducing the costs of mass incarceration. A list of supporting organizations can be found here.

Neither of these two policy recommendations will by themselves solve the problem of racial inequality in criminal justice. As recent commentaries have noted, significant decreases in the prison population will require changes in sentencing policies for a broad range of offenses other than nonviolent drug crimes, with a special focus on mandatory-minimum sentencing.

Indeed, it is unrealistic to expect that such a complicated matter can be completely addressed by any amount of legislation. Structural changes must be accompanied by changes at the cultural and personal levels, as suggested by the recent push to deploy police body cameras, which is partly designed to deter racially biased interactions between officers and citizens.

However, legislators must not be immobilized by a desire to transform the system in a single maneuver. And each new law can help steer societal forces in the right direction, challenging individuals, law enforcement agencies, and other institutions to evaluate their own internal biases. While the process, already decades old, will take yet more time, serious legislative reform of our criminal justice system is a precondition for true racial equality in America.