Perspectives September 28, 2015

A Prophet Ignored in His Own Land: Andrey D. Sakharov

Under Vladimir Putin, the Kremlin has suppressed the legacy of the Soviet Union’s leading dissident, whose warnings against unconditional détente remain relevant today.

Under Vladimir Putin, the Kremlin has suppressed the legacy of the Soviet Union’s leading dissident, whose warnings against unconditional détente remain relevant today.

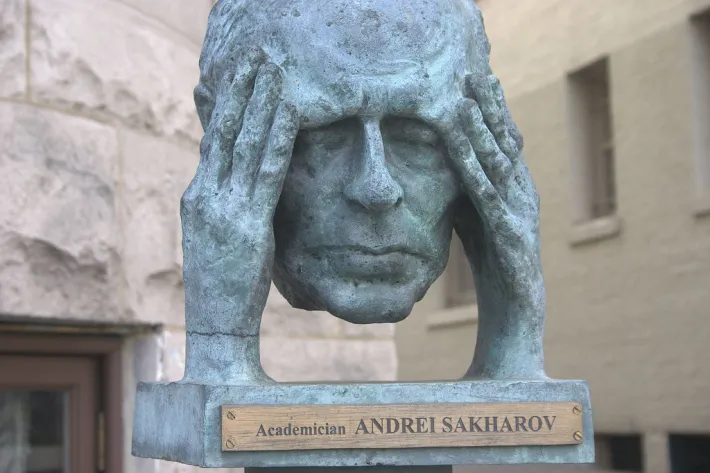

This piece of art is found outside The Russia House Restaurant & Lounge in Washington, DC. Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov (May 21, 1921 – December 14, 1989) was a Soviet nuclear physicist, dissident and human rights activist. Sakharov was an advocate of civil liberties and reforms in the Soviet Union. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1975. Photo courtesy of David Gaines.

It’s September, and students in Russia have returned to class, to be taught a version of history that places Joseph Stalin firmly in the ranks of their country’s honored leaders. While not portrayed as a demigod, Stalin is described as wise, decisive, a model Russian patriot.

That a tyrannical mass murderer is presented as a worthy, if perhaps flawed, statesman tells us a great deal about the kind of national mindset Vladimir Putin seeks to inculcate. It also explains the absence from the history texts of a truly great figure, Andrey Dmitriyevich Sakharov.

Today Sakharov is recalled in the West as a dissident and Nobel peace laureate. In Russia, however, he has been relegated to the status of nonperson. Putin and other leaders carefully avoid mentioning him, his legacy, and his views. The organizations that were launched to promote his principles are harassed and placed on the “foreign agents” list. In an age of flourishing new media, Russians are ironically less likely to know what Sakharov stood for than was the case under Soviet censorship, when samizdat literature was reproduced on manual typewriters to reach an audience of a few hundred.

In fact, Sakharov was an imposing global presence from the mid-1960s until his death in 1989. His stature derived from his prominent role in the development of the Soviet nuclear arsenal. He was sometimes called the “father of the hydrogen bomb,” and because of the respect he enjoyed in the global scientific community, his views on arms control carried enormous weight.

His initial forays into political dissent consisted of cautious statements about the importance of weapons treaties between Washington and Moscow. But the more he thought about arms control, the more closely he looked at his own society. And soon he was making caustic comments about the yawning gap between Soviet boasts on the achievements of socialism and the reality of Soviet backwardness.

“The more obvious the complete failure to live up to most of the promises in [Soviet] dogma, the more insistently it is maintained,” he wrote, while decrying the permanent militarization of the economy.

A critic of America’s military intervention in Vietnam, Sakharov was nevertheless appalled by the scenes that accompanied the fall of Saigon to Communist forces and the subsequent reign of terror under the Communist victors in Vietnam and Cambodia.

He eventually came to see the system that prevailed in the Soviet Union as inherently repressive. Sakharov attributed Russia’s epidemic of alcohol abuse to the leadership’s having purged the governing system of moral considerations. He said it was “important that our society gradually emerge from the dead end of unspirituality.” He spoke of the need for the “systematic defense of human rights and ideals, and not a political struggle, which would inevitably incite people to violence, sectarianism, and frenzy.”

He supported the 1968 Prague Spring, with its goal of “socialism with a human face,” and condemned the subsequent Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia, which snuffed out the reform spirit in the Soviet bloc for years.

During Sakharov’s time as political dissident, a major debate revolved around the kind of détente that should emerge between the United States and the Soviet Union. Most foreign affairs specialists urged a rapprochement that was value neutral, limited to issues of diplomacy, arms control, and trade, and that made no demands on the Soviets to reform a political system defined by its repressive features. This interpretation of détente was embraced by Presidents Nixon and Ford, as well as by Henry Kissinger, the architect of American foreign policy in those years. And, of course, by the Soviet leadership.

Sakharov found this approach unacceptable. Speaking in 1973, he rejected “rapprochement without democratization, rapprochement in which the West in effect accepts the Soviet Union rules of the game.” To avoid the issue of repression, he said, “would mean simply capitulating in the face of real or exaggerated Soviet power.” It would also, he added, “contaminate the whole world with the antidemocratic peculiarities of Soviet society … [and] enable the Soviet Union to bypass problems it cannot resolve on its own and to concentrate on accumulating further strength.… I think that if rapprochement is to proceed totally without qualifications, on Soviet terms, it would pose a serious threat to the world as a whole.” Pressure from dissidents like Sakharov contributed to the inclusion of human rights principles in détente, and specifically in the landmark Helsinki Accords of 1975.

While conditions have changed in important ways since the disintegration of the Soviet Union, many comments that Sakharov addressed to his country decades ago have relevance today. Substitute Putin’s Russia for the Soviet Union, and phrases like “antidemocratic peculiarities” and “rapprochement without qualifications” stand as bitter reminders of just how badly things have deteriorated under the current leadership.

Though never sent to the gulag, Sakharov, along with his family, was harassed by the authorities, and after he criticized the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, he was packed off to house arrest in Gorky. As part of his reform program, Mikhail Gorbachev brought Sakharov back to Moscow and treated him as an important, and respected, critic and adviser. Sakharov in turn supported Gorbachev’s perestroika project, and died believing that his country might be on the brink of important changes.

The changes, many quite important, did come. But Russia today is far different, and in many respects darker, than during the glasnost era. Gorbachev himself has been treated harshly by those who hold power in Moscow. Official historians compare the “weak” Gorbachev unfavorably to the “strong” Stalin, and some members of parliament have demanded that criminal charges be brought against him.

As for Sakharov, the Kremlin has worked hard to make Russians forget that he once ranked among the world’s most eminent figures of political protest. The current leadership is especially determined to ensure that Sakharov’s core goals disappear from the debate: a Russia committed to humane and democratic values, a government that deals honestly with the people, and a country that lives at peace with its neighbors.