Perspectives November 7, 2019

Thirty Years: The Changing State of Freedom in Central Europe

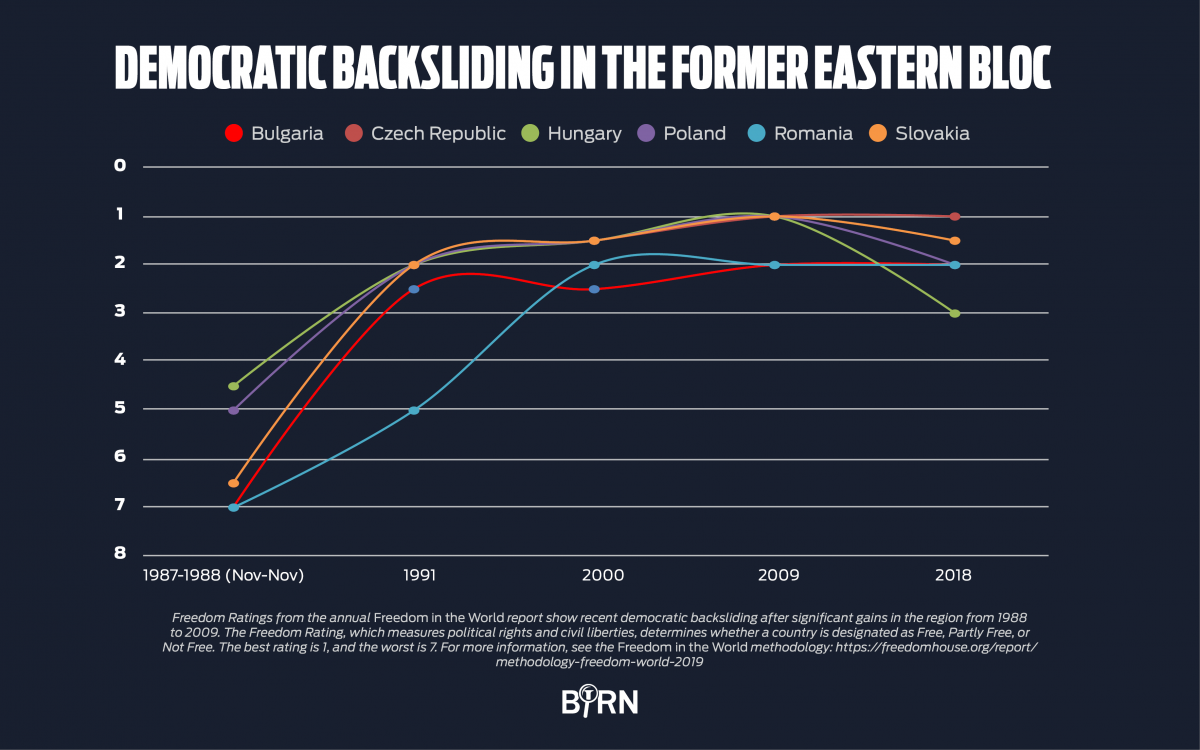

Thirty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, extracts from decades of Freedom in the World reports paint a picture of a region in flux and prone to democratic backsliding.

Brandenburg Gate December 1989 via Wikimeda Commons

Since 1972, Freedom House’s annual Freedom in the World report has evaluated the condition of democracy in every country around the globe. It has tracked many gains and declines in all those years, but 1989 stands out as a singular watershed for freedom, especially in Central Europe.

In a period of just six months, protest-driven popular movements swept away communist regimes in Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary, Poland, and Romania — all of which had consistently been rated “Not Free” by Freedom House.

Within a few short years, East Germany was reunited with the West, and the other former Soviet bloc countries had embraced democratic systems, with competitive elections, freedom of speech, and an array of other civil liberties. All moved ahead on a path to European and Euro-Atlantic integration.

For the next two decades, the anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall and the rest of the Iron Curtain was celebrated as a symbol of democracy’s triumph over tyranny in Europe.

More recently, however, this ritual has been complicated by the deterioration of democratic institutions in each of the Central European countries that made breakthroughs in 1989.

The following excerpts are drawn from the Freedom in the World reports covering 1988, 1990, 2000, 2010 and 2018.

Taken together, they tell the story of a crumbling communist system, the early challenges of the transition to democracy, the achievements of the post–Cold War era, and a new period of setbacks and outright attacks on basic freedoms.

A few major impressions stand out:

- The transition to a democratic political model took place quickly, with most countries conducting multiparty elections, introducing media freedom and abolishing strict communist controls over the economy within a year or two of their revolutions.

- Corruption has plagued every country in the region throughout the post-communist period.

- Civil society organisations proliferated throughout Central Europe, but those dedicated to political reform and honest government have come under state pressure in recent years.

- The development of independent media has proceeded at an uneven pace. In Hungary, the government of Prime Minister Viktor Orban has achieved political domination of the media sector since taking power in 2010, while journalism in other countries has suffered from ownership concentration and growing partisan polarisation.

- There have been major gains for the rule of law since 1989, but the current ruling parties in Hungary and Poland have made a priority of gaining control over the courts, and judicial independence is under threat in other countries as well.

- Some progress has been made in ensuring equal treatment for minorities, though important problems persist. For example, there is political and societal resistance to equal rights for Muslims and LGBT+ people in most countries in the region.

The achievements of 1989 and the years of reform that followed have certainly not been eradicated. Nearly every country in the region is still rated “Free”, and all of those whose regimes fell in that landmark year remain members of NATO and the European Union.

But in the most recent edition of Freedom in the World, Hungary became the first EU member state to be downgraded to “Partly Free” status, and others — Poland in particular — may be headed toward similar declines.

The history of the past 30 years shows that the struggle for democracy is never truly over, and that the fruits of revolutions like those in 1989 must be actively defended.

If the anniversary was once a celebration of a job well done, it should now serve as inspiration for new and sustained effort.

1988

BULGARIA

The same man has essentially ruled over the system since 1954. Elections at both the national and local levels have little meaning, but nonpartisan independents have recently been allowed to run in local elections.

All media are under absolute control by the government or its party branches. Citizens have few if any rights against the state. There are hundreds or thousands of prisoners of conscience, many living under severe conditions. Citizens have little choice of occupation or residence.

The most common political crimes are illegally trying to leave the country, criticism of the government and illegal contacts with foreigners.

CZECHOSLOVAKIA

Czechoslovakia is a Soviet-style, one-party communist state, reinforced by the presence of Soviet troops. Elections are non-competitive, and there is essentially no legislative debate. Polls suggest passive opposition of the great majority of people to the governing system.

Media are government- or party-owned and rigidly censored. There is a general willingness to express dissent in private, and there are many serious, if small, underground publications.

There are a number of prisoners of conscience; exclusion of individuals from their chosen occupations and short detentions are more common sanctions. The beating of political suspects is common, and psychiatric detention is employed.

HUNGARY

Hungary is ruled as a one-party communist dictatorship. Although there is an elective national assembly as well as local assemblies, all candidates must be approved by the party, and the decisions of the politburo are decisive.

Within this framework, recent elections have allowed choice among candidates. Independents have been elected, and in many cases runoffs have been required. Parliament has come to take a more meaningful part in the political process.

The group rights of the Hungarian people are diminished by the government’s official acceptance of the right of the Soviet government to intervene in the domestic affairs of Hungary by force.

POLAND

Poland is a one-party communist and military dictatorship. Assembly elections in 1985 allowed some competition. All candidates must support the system.

More generally, in recent years a few non-party persons have gained election to the assembly, and parliament sometimes refuses to go along with the government. In 1987, the government allowed itself to be defeated on a major referendum.

The Polish newspapers are both privately and government owned; broadcasting is government owned. Censorship is pervasive, but legal media have opened their discussion to a wide range of opinions.

Underground publication on a massive scale exists in a variety of fields. Private expression is relatively free. Although there are no formal rights of assembly or organisation, the government has accepted tacitly the concept of a legitimate opposition, even perhaps of opposition parties.

ROMANIA

The media include only government or party organs; self-censorship committees replace centralised censorship. Private discussion is guarded; police are omnipresent. Dissenters are frequently imprisoned.

Forced confessions, false charges, and psychiatric incarceration are characteristic. Treatment may be brutal; physical threats are common. Many arrests have been made for attempting to leave the country or importing foreign literature (especially Bibles and publications in minority languages).

1990

BULGARIA

In 1990, Bulgarians had the means to change their government through democratic mechanisms, and national elections in June were generally free and fair, despite some irregularities.

The campaign prior to the vote was marred by violence and intimidation of opposition candidates and their supporters by the ruling party, which won the election.

Authorities arrested several former officials, including former leader Todor Zhivkov, and several officials charged with running labour camps where prisoners were tortured and killed in the 1950s and 1960s. Former communists remained in key security and judicial posts.

Citizens freely express their views, and there is de facto freedom of assembly. Independent political parties were legalised in 1990. The government-controlled media generally follow the Bulgarian Socialist Party line.

Dozens of independent newspapers and publications have been created, although throughout the year the government’s monopoly on printing facilities and newsprint was used to keep their circulation down.

A few years before, Turks were forced by the government to adopt Bulgarian (Slavic) surnames, and the open practice of Islamic customs was banned.

In 1990, the new government passed legislation safeguarding the rights of Turks, and in March, parliament adopted a measure allowing Turks to restore their Turkish surnames.

Nevertheless, there were several huge anti-Turkish demonstrations, and the issue remains explosive.

CZECHOSLOVAKIA

The Civic Forum — headed by Vaclav Havel, who had been elected President on December 29, 1989 — won free multiparty parliamentary elections in June.

But the post-communist government had to grapple with a number of difficult issues, among them the pace and scope of free-market reforms, growing nationalism in Slovakia, the surprising resilience of the communists and the withdrawal of Soviet troops.

In August, tens of thousands of Slovaks demanding an independent state demonstrated at a rally.

In addition to demanding greater language rights, Slovak nationalists also raised uneasy feelings and outrage in the Czech Republic by bringing into the open revisionist views of Slovakia’s history from 1939 to 1945, when Hitler created an “independent” state under Roman Catholic Monsignor Jozef Tiso as president. Commemorations in 1990 of Tiso as a “hero of the Slovak nation” embarrassed the government.

In September, the republics announced sweeping plans that would relieve the federal government of some authority and allow them to draw up their own constitutions. Responsibility for key areas such as energy and metallurgy was to be devolved to the republics.

In May, investigators were told to step up the complicated task of identifying and ferreting out the secret police and web of informants who terrorised people under the communist regime.

Two cabinet ministers — the minister of information and the minister of agriculture — resigned after it was discovered they had links to the secret police.

The Havel government, many of whose members were former political prisoners, also sought to improve prison conditions. In January, President Havel amnestied about two-thirds of all Czech prisoners.

The independent press is free from government interference and newspapers represent diverse viewpoints. Previously banned books are openly available and legal.

In April, Pope John Paul II visited the country to find a revitalised Catholic church. Between January and April, all the 13 bishoprics, some of which had stood vacant for thirty years, were filled.

HUNGARY

In 1990, Hungary continued its smooth political transition from communist rule to a genuine multiparty democracy.

The country’s first free national elections in more than 40 years resulted in a coalition government led by the centre-right Hungarian Democratic Forum, and the emergence of a well-organised parliamentary opposition.

POLAND

In 1990, Lech Walesa, who guided Solidarity from being an underground movement to leading Eastern Europe’s first non-communist government, was elected president of Poland. […]

By April, there were open tensions within the Solidarity movement over the pace of the country’s transition to democracy, as well as its efforts to install a free-market economy.

By late June, the split in the Solidarity movement was becoming wider, with competing wings calling for the dissolution of the 150-member national Civic Committee, the organisation set up by Walesa as the intellectual and political soul of the movement.

During an acrimonious meeting, 63 Solidarity leaders critical of Walesa signed a letter calling for the committee to disband.

The squabbling turned personal. Responding to charges that he was sympathetic to communists, [Adam] Michnik responded, “If I am a crypto-communist, my respected antagonists, then you are swine.”

The campaign itself was marked by personal attacks, not debates on issues. Walesa was accused of dictatorial leanings; [Stanislaw] Tyminski called the prime minister a traitor, and newspapers and both Solidarity factions publicly questioned Tyminski’s sanity and the acknowledged presence of former secret policemen on his campaign staff.

Although Walesa’s margin was impressive, there were heavy costs in the campaign. He alienated many of the intellectuals who were once his compatriots and partners, offended by his statements that he would be willing to rule by fiat.

The austerity package that went into effect in January allowed prices to rise on a monthly basis, and after the first two months prices skyrocketed by 78 per cent.

Wages were restrained by heavy taxes, resulting in a drop of living standards. Hyperinflation was stopped, stores filled up with goods, and the private sector eventually boosted its share of gross domestic product to 35 percent.

ROMANIA

In January, the National Salvation Front (FSN) announced several reforms. The government stopped the export of foodstuffs and oil, which had led to massive shortages under Ceausescu, and scrapped the hated “systematisation” plan, a forced resettlement programme that had led to the destruction of whole villages.

President Ion Iliescu also announced the abolition of the death penalty and the dissolution of the dreaded Securitate, Ceausescu’s secret police. Farmers were allowed to own small plots as long as they worked them themselves and sold a certain amount of produce to the state.

There was also an explosion of ethnic violence, as army tanks and troops were used to separate rival mobs of Romanians and ethnic Hungarians in the Transylvanian town of Targu Mures.

In several days, six people were killed and hundreds injured. The violence occurred after a weeklong strike by 280 Hungarian students at the town’s medical institute who demanded to be taught in Hungarian and equal representation for Hungarians in the national senate.

Romanians went to the polls in May presidential and parliamentary elections that were considered “generally” free and fair after a campaign that was marked by intimidation and violence against the opposition by the FSN, which emerged an overwhelming winner.

Laws placed restrictions on freedom of assembly and association. The government acknowledged in October that it was using “a few thousand” members of the former secret police to help maintain public order. There were allegations that the Securitate operates within the military under a new name, Siguranta.

State-run television and newspapers sought to be more balanced in their coverage, but generally reflect official positions.

The independent press and party newspapers have been subject to closure and intimidation, and the government has withheld access to newsprint and held up distribution.

Diplomats and politicians have maintained that telephone taps have resumed. Despite changes in the law, literature is still confiscated at the border.

2000

BULGARIA

The 1996 presidential, 1997 parliamentary and 1999 local elections were regarded as free and fair by international election observers.

According to a June survey conducted by the Noema polling agency, one quarter of the women in Bulgaria are victims of domestic violence, and two-thirds of those never seek help. Trafficking of women for prostitution remains a serious problem.

The constitution guarantees freedom of the press. There were no reports of harassment against journalists in 2000.

Some positive reforms included the launch of a nationwide programme in the Turkish language by the Bulgarian state television; a proposal by the government to establish a Balkan Media Academy in Sofia to train journalists to work for independent media in the Balkan region; and the first private broadcast television operator, Rupert Murdoch’s Balkan News Corporation, with nationwide coverage.

CZECH REPUBLIC

In 1999, the Czech Republic joined NATO and ratified the EU social charter. The Czech Republic has a solid record of free and fair elections.

A scandal in the ruling Czech Social Democratic Party (CSSD), efforts to meet EU accession requirements and a power struggle between Havel and the CSSD-Civic Democratic Party alliance also marked the year.

The government reformed the commercial code and announced plans to privatise remaining state assets.

HUNGARY

In 2000, Prime Minister Viktor Orban declared the end of Hungary’s post-communist transition when output and real wages reached 1989 levels.

The UN Committee on Trade and Development called Hungary’s economy “the most open” in the region, and the European Commission praised Hungary’s progress in fulfilling EU accession criteria.

In September, the government announced a two-year, $8.2 million programme to provide vocational training and other programmes for Roma youth. The Interior Ministry has pledged to deal with police violence against Roma by providing special training and hiring more Romany police officers.

Independent media thrive in Hungary, but oversight of state television and radio remains a controversial issue.

A 1996 media law requires ruling and opposition parties to share appointments to the boards overseeing state television and radio. But critics charge that the coalition government has manipulated the law by approving boards composed solely of its supporters, and has thereby gained undue influence over hiring and reporting.

The constitution guarantees religious freedom and provides for the separation of church and state. There are approximately 100 registered religious groups — primarily Roman Catholics, Lutherans, Calvinists and Jews — to which the state provides financial support for worship, parochial schools and the reconstruction of property.

POLAND

In 2000, the state returned approximately $2 billion in communal property — including synagogues, schools and cemeteries — to Polish Jews, and the first synagogue in Oswiecim (Auschwitz) opened since the end of World War II.

The country’s Roman Catholic bishops presented a letter in 2000 in which they asked for forgiveness “for those among us who show disdain for people of other denominations or tolerate anti-Semitism”.

Poland’s controversial 1998 lustration law requires candidates for political office to confess any cooperation with the communist-era secret police. If a candidate denies cooperation and the lustration court determines he lied, the law bars him from public office for 10 years.

Prior to the 2000 presidential election, for example, independent candidate Andrzej Olechowski admitted collaborating with the secret police in the early 1970s.

When Alexander Kwasniewski and Lech Walesa denied any spying, however, the State Protection Office (UOP) challenged them. The court ultimately cleared them of wrongdoing, but charges that the UOP’s efforts were politically motivated cast doubt on the integrity and efficacy of the lustration process.

ROMANIA

The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe judged the 2000 presidential and parliamentary elections “free and generally fair”. Voter turnout was at 57.5 per cent, 20 per cent lower than in the 1996 elections.

The Chamber of Deputies voted in June to decriminalise homosexuality, although people can still be jailed for “abnormal sexual practices” in public.

The legislation to change Article 200 of the 1996 Penal Code, which punishes displays of public homosexuality, still needs Senate approval.

Corruption is endemic in the government bureaucracy, civil service and business.

SLOVAKIA

The Czech and Slovak republics celebrated the end of their “velvet divorce” in 2000.

Corruption took the spotlight in 2000 when allegations of abuse of office touched the police, parliament, [former Prime Minister Vladimir] Meciar, and even [then Prime Minister Mikulas] Dzurinda.

In July, parliament passed in its first reading extensive constitutional reforms designed, in part, to strengthen judicial independence, improve efficiency and harmonise Slovak law with other Western legal systems.

2010

BULGARIA

The 2009 parliamentary elections were held under new rules enacted less than three months before the voting.

The changes created 31 single-member constituencies that varied widely by population, leaving the other 209 seats under the existing system of regional proportional representation. Vote buying remained a problem, although open discussion of the practice reportedly helped to alleviate its effects.

Corruption is a serious concern in Bulgaria. The European Commission’s July 2010 progress report hailed the Citizens for the European Development of Bulgaria (GERB) government’s “strong reform momentum”, but warned that major substantive improvements were still necessary.

Bulgarian media have benefited from significant foreign investment, but political and economic pressures sometimes lead to self-censorship. Although the state-owned media have at times been critical of the government, ineffective legislation leaves them vulnerable to political influence.

A member of the ruling GERB party was forced to resign as deputy speaker of parliament in July 2010 after being accused of trying to quash a report by the privately owned Nova TV on possible corruption among customs officials.

Bulgaria’s judiciary has benefited from a series of structural reforms associated with EU accession.

However, the July 2010 European Commission report urged the government to push forward with a judicial reform strategy unveiled in June, noting that increased police and prosecutorial efforts to combat corruption and organised crime had often foundered in the courts, with cases subject to indefinite procedural delays and dismissal on technicalities.

While some organised crime figures have been convicted, their cases were resolved through plea bargaining and inordinately lenient sentences rather than successful trials.

CZECH REPUBLIC

Corruption and lack of transparency remain core structural problems, and government reforms have been slow. The authorities have consistently failed to fully investigate and follow through on corruption accusations brought against politicians.

A 2009 amendment to the criminal code bans the publication of information obtained through police wiretaps, even in cases of public interest.

In October 2010, Jiri Gaudin — a member of the far-right National Party — received a suspended sentence of 14 months in prison for inciting racial hatred through a publication called “The Final Solution to the Gypsy Question”, in which he advocated the expulsion of the country’s entire Romany population.

Internet access is unrestricted.

Prisons generally meet international standards, though abuse of vulnerable prisoners serving life sentences remains a problem.

In an effort to address overcrowding, amendments to the criminal code adopted in January 2010 allowed for prisoners to be placed under house arrest, but the programme suffered from inadequate staffing and a shortage of monitoring devices.

HUNGARY

In April 2010 parliamentary elections, the conservative Alliance of Young Democrats–Hungarian Civic Union (Fidesz) and its junior partner, the Christian Democratic People’s Party, won a two-thirds majority in the National Assembly.

The resulting government, headed by Fidesz leader Viktor Orban, passed a series of laws that consolidated its control over the media and other institutions.

In November, the Fidesz government announced plans to disband the independent Fiscal Council, which is responsible for overseeing budgetary policy.

Also in June, the Fidesz government announced a package of media legislation that, after passing through the parliament over the subsequent months, threatened to tighten government control over print, broadcast, and online media.

The overhaul merged existing regulatory bodies into a single entity, the National Media and Infocommunications Authority (NMHH), and created a Media Council under the NMHH that would have the power to impose fines of up to $950,000 on outlets for violations of vaguely defined content rules.

While foreign ownership of Hungarian media is extensive, domestic ownership is highly concentrated in the hands of Fidesz allies.

In November, the government passed a law that will force journalists to reveal their sources for articles concerning national security or public safety issues.

In October 2010, the Constitutional Court rejected a government-backed law imposing a 98 per cent retroactive tax on public-sector severance payments exceeding two million forints ($10,200).

The government responded in November by amending the constitution to curtail the court’s jurisdiction over budgetary and taxation matters and passing the tax law a second time.

Same-sex couples can legally register their partnerships. However, homosexuals remain a target of discrimination and occasional violence.

POLAND

President Lech Kaczynski and dozens of other Polish dignitaries were killed in an April 2010 plane crash in Russia, but Poland’s robust political institutions ensured the orderly and democratic replacement of all deceased officials.

Corruption remains a problem and often goes unpunished.

Control over TVP (state broadcasting) has been the subject of political disputes in recent years, as several bills on the station’s funding have been passed by the parliament and then vetoed by the president.

Poland has an independent judiciary, but courts are notorious for delays in administering cases. State prosecutors have proceeded slowly on corruption investigations, contributing to concerns that they are subject to considerable political pressure.

Ethnic minorities generally enjoy generous protections and rights under Polish law, including funding for bilingual education and publications. They also receive privileged representation in the parliament, as their political parties are not subject to the minimum vote threshold of five per cent to achieve representation.

Some groups, particularly the Roma, are subject to discrimination in employment and housing, racially motivated insults, and, less frequently, physical attacks.

ROMANIA

Prime Minister Emil Boc of the ruling Democratic Liberal Party implemented sharp spending cuts and tax increases in 2010, aiming to reduce the budget deficit and comply with a 2009 international loan agreement.

The measures prompted repeated protests by public-sector workers, but the government survived a series of no-confidence motions brought by the opposition.

An EU progress report in July criticised Romania for showing a lack of commitment on anti-corruption and judicial reforms.

The government’s lack of effective conflict-of-interest safeguards and procurement procedures were also cited in the report.

Among several other ongoing cases against senior law enforcement and political figures, prosecutors in May charged former Prime Minister Adrian Nastase with taking bribes during his time in office.

The constitution protects freedom of the press, and the media are characterised by considerable pluralism. However, a weakening newspaper market led some foreign media companies to withdraw from the country in 2010.

Political bias at state-owned media is a concern, and private outlets are heavily influenced by the political and economic interests of their owners.

The government does not restrict academic freedom, but the education system is weakened by unchecked corruption.

The courts continue to suffer from serious staffing shortages, and criminal defendants have been able to initiate lengthy delays in their cases, though legislation passed during 2010 eliminated some common stalling mechanisms.

The EU report criticised the judicial disciplinary system, citing lenient sanctions and the paucity of cases opened.

SLOVAKIA

Supreme Court President Stefan Harabin resisted efforts at judicial reform during the year and continued his attacks on the press, filing a $290,000 libel suit against Radio Expres.

The new government took some steps to correct its predecessor’s lack of transparency regarding public procurement processes, initiating the online publication of information related to state contracts.

Transportation Minister Ivan Svejna of Most-Hid resigned in October over an apparent conflict of interest involving state contracts awarded to his private consulting firm, Hayek Consulting.

Radicova ordered the dismantling of the National Agency for the Development of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (NADSME), which is accused of misplacing millions of dollars in state funds, and at year’s end the European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF) was investigating NADSME’s use of 50 million euros in EU funding.

Slovakia was ranked 59 out of 178 countries surveyed in Transparency International’s 2010 Corruption Perceptions Index.

Slovakia’s media are largely free but remain vulnerable to political interference. Journalists have faced an increasing number of verbal attacks and libel suits by public officials.

In the run-up to the 2010 parliamentary elections, Prime Minister Robert Fico’s government continued to pressure the state-owned public broadcaster, Slovak Television, to provide favourable coverage of official events.

In May 2010, Slovakia’s first gay rights rally was attacked by neo-Nazi counterdemonstrators, and the police were widely criticised for failing to provide adequate security.

2018

BULGARIA

In January, the parliament overrode a presidential veto and adopted legislation that would establish a new commission tasked with combating official corruption.

In 2017, the Constitutional Court struck down the law on compulsory voting.

There have been multiple peaceful transfers of power between rival parties through elections since the end of communist rule in 1990.

Domestic ownership of media has become more concentrated in the hands of wealthy Bulgarian businessmen, leaving the sector vulnerable to political and economic pressures and limiting the diversity of perspectives available to the public. News outlets often tailor coverage to suit the interests of their owners.

Organised crime is still a major issue, and scores of suspected contract killings since the 1990s are unsolved.

CZECH REPUBLIC

President Milos Zeman won re-election in January, defeating Jiri Drahos in the second round of voting.

An online disinformation campaign, which analysts believe emanated from Russia, led to the circulation of rumours on social media that Drahos had worked with the secret police during the communist era, among other smears.

After nearly nine months of negotiations, in July, Prime Minister Andrej Babis formed a coalition government consisting of his ANO 2011 party, the Czech Social Democratic Party, and the Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia.

Verbal and physical attacks, harassment and intimidation of journalists were problems in 2018. Both Zeman and Babis have made inflammatory remarks about the press, contributing to a hostile environment for journalists.

Anti-Islamic attitudes have increased in the wake of the refugee crisis confronting European states, and the country’s legal battle with the EU about accepting refugee quotas.

The populist and anti-immigration SPD relied heavily on Islamophobic rhetoric during the 2017 election campaign, calling Islam “incompatible with freedom and democracy” and purchasing billboards that read “No to Islam”.

HUNGARY

Hungary’s status declined from “Free” to “Partly Free” due to sustained attacks on the country’s democratic institutions by Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s Fidesz party, which has used its parliamentary supermajority to impose restrictions on or assert control over the opposition, the media, religious groups, academia, NGOs, the courts, asylum seekers and the private sector since 2010.

Fidesz regained its two-thirds majority in April’s parliamentary elections. The party’s campaign was characterised by harsh anti-migrant rhetoric and characterisations of Orban as a defender of “traditional” Christian values in Europe.

The opposition’s ability to challenge Fidesz was significantly hampered by the ruling coalition’s mobilisation of state resources, media bias and restrictions that affected opposition access to the advertising market.

Constitutional amendments enacted during the year included provisions that make it the obligation of all state organs to defend Christian culture, and established new legal grounds for constraints on freedom of assembly.

Pro-government media outlets have published lists of activists, academics, programmes and institutions and labelled them as “Soros agents” or “mercenaries”.

The ideological attacks have targeted gender studies programmes, but also broader research on inequality, or simply criticism of various government proposals. The effort has encouraged self-censorship.

The government’s decision to assume control of a large portion of funding for the Hungarian Academy of Sciences left the entity, the leading network of research institutions in the country, uncertain about its future.

POLAND

In February 2018, parliament passed a law criminalising claims of Polish complicity in crimes committed during the Holocaust, carrying a potential prison sentence of up to three years. The government walked back the law following an international outcry, making it a civil offense punishable by fines.

Amendments to the electoral code endangered the independence of the National Electoral Commission (PKW), which manages elections and oversees party finances, by shifting responsibility for many of its nominations to institutions controlled by the ruling Law and Justice party.

The reform underwent no public consultation and was criticised by the PKW head and opposition lawmakers.

The judicial reforms have raised concerns among EU member states about the independence of Poland’s judiciary and its adherence to the EU’s values.

Members of the LGBT community continue to face discrimination. Hate crimes, particularly against Muslims or people believed to be Muslim by their attackers, have risen significantly over the last few years.

According to a 2018 survey of people who identify as Jewish, carried out and published by the EU Agency for Fundamental Rights, a large majority of respondents in Poland said anti-Semitism in public life was a significant, increasing problem.

ROMANIA

Laura Codruta Kovesi, head of the National Anti-corruption Directorate, was forced out of office in July after the Constitutional Court upheld the justice minister’s request for the president to dismiss her.

The directorate, which had aggressively prosecuted corruption among leading Social Democratic Party officials and others, was headed by an interim leader at year’s end.

Also in July, parliament approved changes to the criminal code that were criticised for weakening safeguards against corruption. President Klaus Iohannis objected to the proposed changes, and the Constitutional Court ruled in October that many of the amendments were unconstitutional.

The government generally does not restrict academic freedom, but the education system is weakened by widespread corruption and politically influenced appointments and financing.

In 2018, the government was criticised for funding changes that appeared to reward underperforming universities for their political support while punishing successful universities known for challenging government education policies and fostering dissent.

Romania’s constitution guarantees freedom of assembly, and numerous peaceful public demonstrations were held during 2018. However, a large protest against government corruption in August was met with tear gas and police violence.

SLOVAKIA

In February, investigative reporter Jan Kuciak and his fiancée were murdered at their home in southern Slovakia. It was the first time in Slovakia’s modern history that a journalist was killed because of their work.

Kuciak had been working on a report that uncovered alleged links between the Italian mafia and Prime Minister Robert Fico’s office.

The murder shocked the country and prompted the biggest demonstrations since the fall of communism. Tens of thousands of people took to the streets, demanding an independent investigation and the resignation of the prime minister, the interior minister and the head of the police. The protesters also called for early elections.

There have been regular alterations of parties in government in the last two decades. In November 2018, opposition and independent candidates defeated incumbents supported by the Direction–Social Democracy party (Smer-SD) in most major cities in local elections.

NGOs came under pressure from Fico who, following public demonstrations after the Kuciak murder, accused them of organising anti-government protests with the aim of “overthrowing” the legitimate government.

Fico linked the organisers to George Soros, a Hungarian-American billionaire and philanthropist who has been scapegoated by nationalist and extremist politicians in several other countries, and argued that NGOs needed to be under closer scrutiny.

In October, the parliament adopted a law requiring NGOs to register with state authorities. Despite initial fears that the law would be similar to the restrictive “foreign agent” laws in Russia or Hungary, the adopted version does not contribute an additional burden to NGOs’ activities.

This article first appeared on Reporting Democracy, a cross-border journalism platform run by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network.

Zselyke Csaky, Isabel Linzer, Shannon O’Toole, Tyler Roylance, Nate Schenkkan, Charlotte Drath, and Ishya Verma contributed to this post.

Read More:

Montenegro, an EU Accession Front-Runner, Moves Backward on Media Freedom

Perspectives

September 20, 2018