The immediate future of internet freedom will depend on how governments deploy incentives for and controls over the next wave of technological innovation.

Key Findings

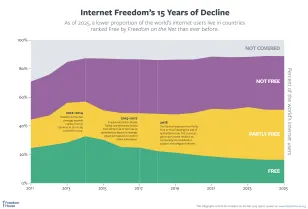

Global internet freedom declined for the 15th consecutive year. Of the 72 countries assessed in Freedom on the Net 2025, conditions deteriorated in 28, while 17 countries registered overall gains. Kenya experienced the most severe decline of the coverage period, after authorities responded to nationwide protests over tax policy in June 2024 by shutting down internet connectivity for around seven hours and arresting hundreds of protesters. Bangladesh earned the year’s strongest improvement, as a student-led uprising ousted the country’s repressive leadership in August 2024 and an interim government made positive reforms. China and Myanmar remained the world’s worst environments for internet freedom, while Iceland held its place as the freest online environment.

Half of the 18 countries with an internet freedom status of Free suffered score declines during the coverage period. Only three countries in this group received improvements. People in Georgia experienced the most significant decline in the Free cohort, followed by Germany and the United States, as the ruling Georgian Dream party enacted repressive measures targeting civil society. Authorities in Germany pursued criminal prosecutions against people who criticized politicians, while threats from far-right actors further encouraged self-censorship online. In the United States, growing restrictions on civic space threatened to stifle digital activism, marked by the detention of foreign nationals for nonviolent online expression.

Control over online information has become an essential tool for authoritarian leaders seeking to entrench their regimes. Governments in the countries that suffered the most extreme declines over the 15 years of global deterioration in internet freedom—Egypt, Pakistan, Russia, Turkey, and Venezuela—intensified their control over the online environment in response to challenges to their rule. Authorities in these settings expanded restrictions on content, escalated surveillance of electronic communications, and imposed more severe penalties on those who expressed dissent online, particularly during protests and elections. The pattern illustrates how digital repression has proven essential for regime security in authoritarian states.

Online spaces are more manipulated than ever, as authorities seek to promote favored narratives and warp public discourse. Of the 21 indicators covered by Freedom on the Net, the one that assesses whether online sources of information are manipulated by the government or other powerful actors has undergone the most consistent global decline over the past 15 years. Information manipulation campaigns have reshaped online spaces, with common methods including paid commenters who masquerade as ordinary internet users, news sites mimicking trusted outlets, misleading content generated by artificial intelligence (AI), and prominent social media influencers who post progovernment content without clear or formal affiliation.

The immediate future of internet freedom will depend on the ways in which governments deploy and regulate new technologies. Governments are overseeing investments in their domestic AI industries that will shape how people interact with chatbots, synthetic media, and other AI-enabled products, with important implications for privacy and free expression in countries where safeguards are lacking. Advances in satellite-based internet connectivity are bringing many communities online, particularly in rural and war-torn areas, exposing satellite service providers to government pressure regarding surveillance and censorship. Online anonymity, an essential enabler for freedom of expression, is entering a period of crisis as policymakers in free and autocratic countries alike mandate the use of identity verification technology for certain websites or platforms, motivated in some cases by the legitimate aim of protecting children.

An Uncertain Future for the Global Internet

The internet is more controlled and more manipulated today than ever before. Global internet freedom declined for the 15th consecutive year in 2025, as authoritarian governments employed censorship and offline repression to quash protests that were organized online, and people in democracies faced an escalation in constraints on digital expression.

When the Freedom on the Net project was launched in 2011, following a 2009 pilot, there was widespread optimism about the power of information technology to support prodemocracy movements and drive progress for human rights. These hopes were buoyed by the prominent role played by online platforms in Iran’s Green Movement and the Arab Spring that followed. From the outset, however, it was apparent that governments could use the same digital technologies to smother dissent and shape online narratives in their favor.

During this report’s coverage period, from June 2024 to May 2025, conditions deteriorated in 28 of the 72 countries assessed, while 17 countries registered overall gains. The year’s largest decline occurred in Kenya, followed by Venezuela and Georgia. China and Myanmar remained the world’s worst environments for internet freedom. Bangladesh earned the largest improvement, while Iceland retained its status as the freest online environment, followed by Estonia.

Explore the Report

On the Horizon for Human Rights Online

Fifteen years of Freedom on the Net analysis shows that the internet has transformed the ways in which state authorities and other powerful actors assert control over information. Authoritarian rulers have deployed tools of digital repression to strengthen their hold on power, particularly in response to protests or elections that challenge their rule, driving the most precipitous cumulative score declines recorded by the report. And in countries across the democratic spectrum, from the worst autocracies to some of the world’s freest societies, political leaders have sought to manipulate online narratives through increasingly sophisticated methods, often attempting to shape the information space without overt censorship.

The immediate future of internet freedom will depend on how governments deploy incentives for and controls over the next wave of technological innovation. Governments around the world are already ramping up their development of AI ecosystems, pouring huge investments into cloud-computing infrastructure and natural-language and reasoning models. Innovations in satellite-based connectivity will change how people access the internet, while the rise of technical measures to verify the age and identity of people using the internet will dramatically alter the online experience. Freedom of expression, access to information, and privacy should be among the values that guide both regulation and innovation.

Those working to safeguard internet freedom face new headwinds, however. The US government’s decision to dismantle its foreign aid institutions resulted in the termination of its support for internet freedom programming, a long-standing priority across multiple Republican Party and Democratic Party administrations. The cuts entailed the cessation of funding to experts developing anticensorship technology and encrypted communication tools, to people working on human rights issues in the world’s least free environments, and to organizations that assisted journalists, activists, and others under threat for the content they posted online. (Freedom House was among the organizations that were materially affected by the freeze in US foreign assistance, which included the removal of funding for Freedom on the Net and our broader emergency support programs.) The United States has long served as a leading advocate of global internet freedom, and its withdrawal from the vanguard leaves a significant gap.

Fifteen consecutive years of decline should stir alarm among supporters of internet freedom and galvanize remedial efforts in the years to come. Halting and reversing the negative trend will require coordinated action by like-minded allies from government, the private sector, and civil society. As emerging technologies begin to affect the exercise of human rights online, these partners must establish safeguards for free expression and privacy to ensure that any technical innovation leads to improvements for global internet freedom.

Tracking the Global Decline

State responses to mass protests, deepening technical censorship, and threats to free speech in democracies fueled the 15th consecutive year of decline in internet freedom. People in at least 57 of the 72 countries covered by Freedom on the Net 2025 were arrested or imprisoned for online expression on social, political, or religious topics during the coverage period—a record high. In May 2025, a Saudi Arabian court sentenced British citizen Ahmad al-Doush to 10 years in prison, reportedly over a deleted 2018 social media post about Sudan and his association with an exiled Saudi critic, though the sentence was reduced to 8 years in June 2025, after the coverage period. In October 2024, a Belarusian court sentenced Andrei Parotnikau, a political analyst and blogger, to 10 years in prison on trumped-up charges including treason and promotion of extremist activities.

A year of mass mobilization

Protests and large-scale uprisings drove some of the year’s most significant developments, as governments engaged in digital repression to thwart communication about acts of dissent. Across the board, authorities arrested online critics and protest organizers. In the more severe cases, governments pursued wholesale restrictions on internet access.

Kenyan authorities carried out a violent crackdown, contributing to the year’s largest score decline, after people mobilized nationwide and online in June 2024 to protest new tax policies and perceived economic mismanagement. The government imposed an approximately seven-hour internet shutdown—the first such connectivity restriction reported in Kenya—and arrested hundreds of protesters. Arrests and disappearances of online activists and critics continued throughout the coverage period, and some of the detainees reported abuse in custody.

- About the Report

This is the 15th edition of Freedom on the Net, an annual study of human rights online. The project assesses internet freedom in 72 countries, accounting for 89 percent of the world’s internet users. This report covers developments between June 2024 and May 2025. The report uses a standard methodology to determine each country’s internet freedom score on a 100-point scale, with 21 separate indicators pertaining to obstacles to access, limits on content, and violations of user rights. The FOTN website features key developments and data on each country’s conditions.

The Venezuelan government employed a barrage of internet controls ahead of the July 2024 presidential election and in response to mass protests that followed the National Electoral Council’s unsubstantiated announcement that authoritarian incumbent Nicolás Maduro won the election, prompting the second-largest decline in Freedom on the Net 2025. The government blocked wide swathes of the internet—including social media and communications platforms, websites of news outlets and civil society groups, and anticensorship tools—as part of a broader effort to limit online discussion and mobilization about serious irregularities in the vote count. Authorities sought to imprison those who challenged the official narrative, detaining digital journalists and forcibly disappearing people who criticized the government online.

The Serbian government’s response to student-led protests caused that country’s internet freedom status to change from Free to Partly Free. When people took to the streets across the country to call for justice and transparency following the deadly collapse of a train station canopy in Novi Sad in November 2024, authorities detained individuals who spoke out in support of the protests online and employed Cellebrite technology to search the phones of journalists and activists.

Serbians mobilized nationwide to protest corruption following the deadly collapse of a train station canopy in November 2024. The government detained people who supported the protests online, causing Serbia’s internet freedom status to change from Free to Partly Free. (Photo credit: Mirko Kuzmanovic)

Bangladesh received the year’s largest score improvement after a student-led uprising culminated in the ouster of longtime Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina and her repressive Awami League (AL) government in August 2024. In July of that year, the AL government restricted access to mobile internet service for 11 days and blocked a host of social media platforms, even as protesters endured brutal state violence. Conditions improved somewhat after Hasina fled the country. While perceived supporters of the AL faced a concerning pattern of retaliation, an interim government carried out some small-scale reforms, and the general opening of democratic space presented a rare opportunity for the advancement of internet freedom.

Authoritarians impose deeper censorship

Some of the world’s most repressive governments expanded their technical censorship efforts during the coverage period. These measures were often accompanied by the arrest and intimidation of online activists, as well as legal provisions that undermined people’s online privacy.

Censorship intensified in China and Myanmar, which remained the world’s worst environments for internet freedom. Chinese authorities continued to develop the country’s censorship infrastructure, with research from the coverage period finding that provincial-level authorities were vigorously blocking online content—sometimes at a scale 10 times that of the national-level system known as the Great Firewall. Leaked documents confirmed that a Chinese company had exported the technology that supports the Great Firewall to facilitate government censorship in other countries, including Myanmar, where the military regime has worked to crush dissent since a 2021 coup. Myanmar authorities also enacted a cybersecurity law in January 2025 that restricted the operation of anticensorship tools in the country and codified the regime’s de facto censorship practices.

Authorities in Russia ramped up efforts to further isolate Russians from the global internet throughout the coverage period. In the summer of 2024, the government blocked the end-to-end encrypted messaging application Signal and began throttling YouTube, one of the few major social media platforms that had remained unblocked since Moscow’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Later in the year, the government restricted access to websites employing Cloudflare services with the Encrypted Client Hello protocol, which helps safeguard user privacy by concealing information about users’ browsing activity. In May 2025, the government began sporadically shutting down access to mobile internet service across the country, citing concerns about attacks from Ukraine.

In Nicaragua, the authoritarian regime of President Daniel Ortega revoked the .ni domain registrations of independent news websites, the first technical censorship recorded in a multiyear crackdown on press freedom. The country’s internet freedom status was downgraded from Partly Free to Not Free as the government forced online media outlets to cease operations. Moreover, amendments to the cybercrime law that were adopted in September 2024 increased criminal penalties for spreading information that the government deems to be false and empowered authorities to obtain user data from telecommunications firms without a court order.

Pressure in democracies

In a concerning sign, half of the 18 countries with an internet freedom status of Free suffered score declines during the coverage period, while only three received improvements. People in Georgia experienced the most significant decline among these countries, followed by Germany and the United States.

In Georgia, which tied for the second-largest decline in Freedom on the Net 2025, the ruling Georgian Dream party continued its campaign against civil society after a new law on “transparency of foreign influence”—which compelled civil society organizations and online media outlets that receive foreign funding to register with the government—took effect in August 2024. Ahead of the October 2024 elections, law enforcement agencies conducted raids on two Atlantic Council researchers who had studied online influence operations in Georgia. In February 2025, Georgia’s parliament passed amendments to the Law on Assemblies and Demonstrations that introduced criminal penalties of up to 45 days in prison for insulting public officials. The amendments were then used to charge people who criticized the government online after the coverage period.

The German government, led by the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and Christian Social Union (CSU) coalition since the February 2025 elections, has pursued criminal prosecutions against people who made memes about politicians, invoking laws against insult and hate speech. Self-censorship also increased because of intimidation by far-right actors against journalists, professional and legal reprisals against people who criticized the Israeli government online, and concerns about rising antisemitic and anti-Muslim hate speech as well as a reported increase in offline violence and threats against both Jews and Muslims. Meanwhile, hackers with ties to the Russian state launched cyberattacks against the CDU ahead of European Parliament elections in June 2024.

The United States retained its overall status of Free, though growing restrictions on civic space drove a significant decline.

While the United States retained its overall status of Free, growing restrictions on civic space drove the decline in its score. The administration of President Donald Trump detained several foreign nationals for one to two months after revoking their visas over nonviolent online expression, as part of a larger program to arrest and deport noncitizens. The Federal Communications Commission and the Federal Trade Commission threatened or carried out politicized investigations into civil society organizations and media and technology companies, often focusing on their content moderation, editorial decision-making, or forms of speech that are protected by the US Constitution’s First Amendment. More broadly, the administration’s actions have chilled the atmosphere for digital activism.

Modest improvements

Some gains in internet freedom were recorded in countries that ranked Partly Free or Not Free in Freedom on the Net, primarily because their governments imposed less severe restrictions than in the previous coverage period. Ethiopia and Kazakhstan received score improvements after authorities imposed less extensive internet shutdowns than in the previous year and made progress in diversifying their domestic telecommunications sectors. Angola and Zimbabwe experienced marginal gains as government-linked efforts to manipulate online information appeared less common during the coverage period. Around the world, meanwhile, countries continued to expand overall access to the internet. The spread of internet services and increased affordability brought improvements in Morocco, the Philippines, and Uzbekistan. Although such incremental changes are welcome, the governments in question have track records of digital repression and still lack legal and institutional safeguards that would protect free expression and privacy over the long term.

Fifteen Years of Evolution in Internet Controls

The internet has transformed how authorities assert control over information in every political environment, from the world’s most repressive autocracies to robust electoral democracies. Over the past 15 years of Freedom on the Net research, antidemocratic leaders have employed a dizzying array of increasingly sophisticated legal and technical measures to influence and dominate the online landscape, particularly in response to challenges to their rule. Meanwhile, social media platforms that host user-generated content have come to define people’s experience on the internet, and campaigns to manipulate the material on these platforms have become more pervasive and refined. Manipulation campaigns often serve as a means for authorities to shape narratives on the internet without relying on more overt censorship or repression.

Authoritarians refine digital restrictions

Over the past decade and a half, authoritarian regimes have deployed increasingly advanced and widespread measures to control online information in an effort to stay in power. In response to mass protests, political activism, or other challenges to their rule, authoritarian leaders worked to dominate digital environments that were comparatively open when Freedom on the Net analysis began in 2011. From technical censorship to draconian criminal penalties for online dissent, their combined repressive measures drove the sharpest long-term declines in internet freedom among the 72 countries covered by the report. Conditions in some of these authoritarian states now approach those in China, where the Chinese Communist Party has long set the standard for digital authoritarianism, and in Iran, where the regime has sought to establish a similar level of censorship and isolation.

In response to mass protests, political activism, or other challenges to their rule, authoritarian leaders worked to dominate digital environments.

In Russia, which underwent the steepest 15-year decline in internet freedom, President Vladimir Putin has attempted to carve out a sanitized domestic internet while crushing dissent. In the aftermath of widespread antigovernment protests between 2011 and 2013 and the 2014 invasion of Ukraine, Russian authorities laid the groundwork for a “sovereign internet,” a technical and legal project to disconnect Russia from the global network. Early restrictions on the internet were not always effective, leaving space for opposition figures, like Aleksey Navalny and his Anti-Corruption Foundation, to organize and advocate online. Even in 2018, the Kremlin was technically unable to follow through on its declared blocking of Telegram. However, new censorship technology developed under the 2019 Sovereign Internet Law and subsequent legislation, which forced popular platforms to comply with Russian law, granted Putin greater practical control over the online space. By the beginning of Moscow’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the new censorship model was demonstrably more effective, as the regime blocked access to international social media platforms, independent news outlets, and human rights organizations.

Since Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi came to power in a 2013 coup, his government has also developed increasingly complex technical controls aimed at silencing his opponents. During the country’s 2011 revolution, then-President Hosni Mubarak infamously ordered a shutdown of the internet for five days and deployed security forces against protesters. President Sisi’s government has since carried out widespread arrests of dissidents and developed a more targeted censorship and surveillance apparatus, rarely imposing wholesale shutdowns. In 2017, the government deployed deep packet inspection technology to block websites, restricting access to some 600 proxy servers, news outlets, and other sites in a three-year period. The Sisi regime has also surveilled prominent opposition politicians with the aid of spyware tools that enable covert access to infected devices, according to investigations by the Canada-based research group Citizen Lab.

Authorities in Turkey have consolidated an expansive censorship system over the past 15 years, spurred by the 2013 Gezi Park protests, which grew into a nationwide movement organized in part on social media platforms. The protests illuminated how people could use social media to sidestep conventional press censorship. In their aftermath, law enforcement officials escalated efforts to prosecute online journalists and digital activists. Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, then the prime minister and since 2014 the president of Turkey, pressed criminal charges against dozens of people for online insult after the protests, and continued to do so in the decade that followed. Erdoğan’s government has relied on blunt censorship measures, like website blocking and throttling of social media, and enacted new laws to compel online media outlets and platforms to remove content that is critical of the political leadership.

Venezuelan authorities have imposed harsher digital controls in the face of widespread discontent over the country’s interlocking economic and political crises. When Maduro assumed power in 2013, censorship of the conventional media had not yet extended to the internet, enabling a diverse online environment. The regime soon introduced censorship measures, including internet shutdowns and blocking of independent media sites, as a means of curtailing dissent. Some of the worst declines in the country’s internet freedom have coincided with its elections, which were rigged to ensure victory for Maduro and his allies. Venezuelans have responded by protesting in the streets and on digital platforms, triggering brutal state violence, as in the aftermath of the July 2024 balloting described above.

Pakistani authorities have imposed more stringent digital censorship measures to maintain the military establishment’s grip on power and its influence over the country’s elections and civilian governments. The government secured passage of an expansive censorship law in 2016 that gave state agencies greater authority to silence dissent and activism, and installed a website-blocking system to translate that legal authority into technical control. In the decade that followed, the government repeatedly extended the remit of the 2016 law to wider swathes of online speech, particularly social media discussions, and bolstered its own technical capacity for censorship. During the coverage period, Pakistani authorities criminalized the sharing of what they deemed to be false information and deployed Chinese website-blocking technology as part of a barrage of censorship measures aimed at curtailing the reach of former Prime Minister Imran Khan and supporters of his Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf party, who alleged that the military had engineered his removal from power in 2022.

A Pakistani police officer monitors social media in 2017. Over the 15 years of Freedom on the Net analysis, Pakistani authorities have expanded their legal and technical capacity to carry out censorship and surveillance. (Photo credit: Asad Zaidi/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Blunt censorship measures and arrests for online speech have been integral to authoritarians’ efforts to dominate the information space. But these regimes have also turned to more subtle measures, such as the covert manipulation of online discussions to promote favorable narratives. That tactic has become increasingly common across the global internet, influencing autocracies and democracies alike over the past 15 years.

Information manipulation reshapes the internet

State-backed manipulation efforts have drastically altered the information available online in many countries and on the internet as a whole. Over 15 years of Freedom on the Net monitoring, the indicator that evaluates whether online sources of information are manipulated by the government or other powerful actors has declined more than any other of the 21 indicators tracked by the project. Its deterioration has been driven primarily by campaigns that sought to manipulate online information in the government’s favor through paid social media commenters, networks of automated accounts, or other means, and by efforts to compel online media outlets to align their reporting with the government’s interests. While many of these campaigns are orchestrated by domestic political actors, they obfuscate their origin and misrepresent content as authentic and organic. Their cumulative effect has been to undermine public access to reliable information and prompt the passage of poorly crafted anti-misinformation laws that harm freedom of expression.

State-backed manipulation efforts have undermined access to reliable information and prompted the passage of poorly crafted laws that harm freedom of expression.

When this project began, manipulation of online information relied mostly on manual effort, with authorities paying largely anonymous online commenters en masse to spew progovernment talking points and disparage critics. In 2011, troll accounts posted in support of Bahrain’s government, regularly criticizing people who backed widespread protests calling for political reform; Bahraini activists identified the accounts as likely linked to the government. A government-funded public relations agency also created online personas of nonexistent journalists to share government propaganda. In Malaysia, ahead of the 2012 parliamentary elections, the ruling Barisan Nasional coalition deployed a “cyber army” to spread falsehoods about an opposition candidate’s family on social media. In 2014, the Ethiopian government secretly paid bloggers to post progovernment articles and refute criticism of the government across social media.

Over time, social media platforms dedicated more resources to identifying state-backed influence operations, including by updating their terms-of-service provisions regarding state manipulation, hiring teams to address the problem, and bolstering their relationships with academic and civil society researchers who focused on information campaigns. These changes played out unevenly around the globe, with companies initially prioritizing markets in the United States and Europe, in part because of scrutiny from their respective governments regarding foreign influence operations. Moreover, the platforms’ policy shifts prompted complaints from people who claimed that their legitimate content had been removed. And even as global social media platforms enhanced their efforts to identify and remove state-backed manipulation operations, the perpetrators were adopting new tactics and migrating to other platforms.

The rise of private chat-based platforms and increasing adoption of end-to-end encrypted messaging have made manipulation campaigns more difficult to detect and counter. Brazilian researchers uncovered a sophisticated network that was manipulating online narratives on behalf of former President Jair Bolsonaro, in part by laundering assertions from Bolsonaro and his allies through influencers and media outlets across WhatsApp, Telegram, YouTube, and other platforms, so that they passed as authentic expressions of support. The reach of this network enabled the Bolsonaro camp to shape online discussion in his favor during moments of political crisis, such as the aftermath of the January 2023 riots in Brasília.

AI innovation has facilitated the automation of influence operations, lowering their cost and increasing their efficiency. Ahead of the December 2024 presidential election in Ghana, a network of automated “bot” accounts spread messages written with the AI service ChatGPT on several social media platforms, with the aim of promoting the incumbent New Patriotic Party, according to disclosures by OpenAI, the developer of ChatGPT. When tensions between India and Pakistan escalated in the aftermath of a terrorist attack in Kashmir in April 2025, government-linked influencers and commenters in both countries posted waves of inflammatory and escalatory AI-generated content, drowning out reliable sources of news and information.

People in the Philippines cast their votes in May 2025 elections. Particularly during election periods, progovernment influencers paid through an opaque network of public relations firms have been integral to shaping public opinion in the Philippines. (Photo credit: Ryan Eduard Benaid/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

Content manipulation campaigns increasingly use technical tricks to masquerade as trusted sources, particularly by mimicking the names, mastheads, and formats of established news websites. In a December 2024 report, Meta stated that most of the influence operations it had removed from its platforms in the past year had redirected people to such misleading websites. In early 2024, an influence operation linked to Bangladesh’s then-ruling AL party posted content on a number of social media platforms, often imitating news sites and redirecting targets to pages that denigrated the opposition. In October 2024, Singaporean researchers identified a shadowy network of news sites disguised as familiar outlets that were all reportedly registered to a little-known public relations agency; the sites posted news content that appeared to parrot Chinese state media. The imitation news sites used in manipulation campaigns often mass-produce content with AI tools to maintain an illusion of depth and scale.

Political parties and governments also rely on well-known social media influencers to help spread propaganda. In the aftermath of South Africa’s May 2024 elections, a report from the Institute for Security Studies found that the uMkhonto weSizwe Party (MKP) had employed paid influencers to advance the unfounded narrative that the election results were “stolen” and to harass electoral commissioners. Progovernment influencers paid through an opaque network of public relations firms have been integral to shaping public opinion in the Philippines, particularly under the rule of former President Rodrigo Duterte (2016–22) and during the election to choose his successor. These influence networks sometimes persist after their patrons or clients lose office. In 2025, pro-Duterte influencers clashed with those supporting his successor, President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., amid a political feud between Marcos and Vice President Sara Duterte, the former president’s daughter.

Some government efforts to address content manipulation have been counterproductive, ultimately damaging freedom of expression. For example, while certain laws compelled platforms to adjust their algorithms and increase transparency, others criminalized the spread of false information writ large. The latter measures have served as a pretext for illiberal and authoritarian regimes to unjustly penalize their critics. In Ethiopia, authorities have invoked the Hate Speech and Disinformation Prevention and Suppression Proclamation of 2020 to investigate and detain independent journalists in retaliation for their reporting. Kyrgyzstani officials have abused the country’s 2021 Law on Protection from False Information to seek the removal of online reporting that is unfavorable to the government, such as opposition politicians’ allegations that they were tortured in detention. Concurrently, governments from across the democratic spectrum have sought to delegitimize and undermine researchers and fact-checkers who seek to counter information manipulation, forcing many of them to abandon their work.

On the Horizon for Human Rights Online

Conditions for internet freedom over the next decade will be shaped in part by the ways in which governments incentivize and regulate new technologies. Three emerging developments—government-backed AI projects, the rise of satellite-based internet connectivity, and mandatory age-verification systems—will influence the near future of human rights online. But the basic challenges presented by all new technologies have remained the same over the past 15 years: how to protect rights while governing online spaces, and how to encourage innovation while establishing safeguards to prevent societal harms. The universal principles of human rights are still the best tools for navigating these straits. Freedom of expression, access to information, and privacy should guide both regulation and innovation in the years to come.

The universal principles of human rights are still the best tools for navigating the challenges presented by new technologies.

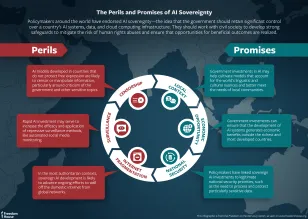

AI sovereignty fuels digital repression

Governments around the world are pursuing ambitious agendas for AI development, and the systems developed or deployed by repressive governments could amplify existing threats to freedom of expression and privacy. As AI companies establish partnerships with governments ranging from democracies to autocracies, they will inevitably face pressure to infringe on human rights, just as telecommunications companies and social media platforms have over the past 15 years. Particularly in the world’s authoritarian states, investment in AI may be misused to enable censorship and surveillance and accelerate governments’ efforts to isolate their populations from the global internet.

AI tools are increasingly embedded in people’s daily lives, the global economy, and government systems. Many governments’ investments in AI are motivated by understandable economic and national security aims. Policymakers worldwide have declared their pursuit of “AI sovereignty,” the idea that governments should retain significant control over AI systems, data, and cloud computing infrastructure, in part by keeping them within their borders or sponsoring the development of their own domestic foundational and large language models (LLMs). Despite the “sovereign” moniker and some leaders’ stated concerns about US or Chinese dominance in the AI industry, many of these efforts rely on equipment or services from US- or China-based companies, which are contracted to supply cloud computing power, semiconductors, and other forms of support.

In authoritarian countries, sovereign AI initiatives could compound existing threats to free expression. Models developed under government oversight may incorporate censorship of certain content, like criticism of the authorities, or reinforce the marginalization of minority groups. Indeed, previous Freedom House research found that AI governance frameworks in China and Vietnam required generative AI chatbots to toe the Communist Party line on sensitive topics. Vietnam has seen a glut of AI investment in 2025, which a Politburo member characterized as a means of affirming the country’s “historical sovereignty . . . in the digital realm.” In Thailand, where criticism of the monarchy is heavily censored, the National Science and Technology Development Agency rolled out Pathumma LLM, a model trained to “understand Thai context and culture,” in early 2025. While developing AI systems that reflect local culture is sensible, there is a clear risk that these initiatives will conflate local culture with state censorship.

AI investments may also facilitate government surveillance, especially in authoritarian countries that lack strong privacy safeguards. The Persian Gulf monarchies have emerged as hubs for AI investment, particularly the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which announced a massive AI infrastructure project in May 2025 in partnership with the United States. The company at the forefront of the UAE’s AI industry, G42, has been scrutinized by US officials for its apparent ties to Emirati and Chinese companies that specialize in surveillance and spyware technology. More broadly, the Emirati government has a long history of deploying such tools for mass monitoring and targeted surveillance of human rights defenders. In these authoritarian environments, rapid AI investment may serve to increase the efficacy and application of repressive surveillance methods.

Sovereign AI development in authoritarian contexts is likely to advance ongoing efforts to wall off the domestic internet from global networks, often referred to as “cyber sovereignty.” In June 2025, the Russian and Belarusian governments launched a plan to develop AI built on “fundamental and traditional values,” reflecting the same justifications that these regimes invoke when restricting access to the global internet. Russian authorities have blocked a wide array of social media platforms and messaging applications, urging users to adopt government-approved alternatives. Ahead of Belarus’s sham January 2025 election, the government ordered the blocking of all websites hosted outside of the country. Iran’s vice president for science announced a national AI platform in March 2025, framing it as part of a “war of chips and algorithms,” and a senior scientist working on the project noted that the platform was designed to function even if Iran were to be completely disconnected from the global internet.

As democracies invest in sovereign AI capabilities in the name of economic opportunity and national security, a key test will be whether policymakers work with the private sector and civil society to establish governance frameworks that protect free expression and privacy. In July 2024, the Brazilian government announced a $4 billion investment plan for sovereign AI that would reflect the country’s values; some $1 billion of the funding was allocated to state-owned technology firms. Brazilian civil society organizations have urged policymakers to embed fundamental rights safeguards as they develop the country’s rules for AI governance. Indian academics and organizations have also called on authorities to put rights-respecting governance measures in place as the government moves forward with AI projects, such as research into open-source LLMs that can operate amid the country’s linguistic complexity, which was announced in January 2025. AI governance measures with human rights safeguards will better position sovereign AI development to fuel innovation tailored to local needs.

Government investment in AI development reflects an understandable desire to ensure that this new wave of technology serves local interests and generates economic benefits outside the richest and most developed countries. But leaders and citizens around the world should not allow these systems to be designed or used to limit freedom of expression or violate privacy; policymakers should work alongside civil society experts to establish human rights safeguards within AI governance frameworks. The firms that provide AI infrastructure and cloud services should conduct human rights due diligence studies, particularly for projects that could impede freedom of expression or expand surveillance capabilities.

Internet freedom from low-earth orbit

A growing sector of satellite-based internet service providers is creating a dramatic shift in how people access the global network, prompting confrontations with governments that seek to control online information. Innovation in the field has lowered the cost of satellite launches, enabling a new model in which providers operate a constellation of many satellites in low-earth orbit that offer wider reach and better connection quality. These advances have brought service to areas that had yet to be reached by fiber-optic or terrestrial mobile infrastructure, or where existing access had been disrupted. However, providers are already facing pressure from authorities to carry out censorship or surveillance or to limit where services are delivered.

As the satellite internet industry expands, service providers are connecting rural communities and people in areas affected by war or natural disasters. Market leader Starlink, a subsidiary of US-based SpaceX, reported six million subscribers across 42 countries in July 2025, four years after it began offering services. Other major providers include Eutelsat OneWeb, a unit of a French firm, and Project Kuiper, owned by the US technology giant Amazon, which launched over 100 satellites in 2025. In Nigeria and Kenya, satellite providers are expanding into rural districts with little access to fixed-line or mobile broadband services, particularly as Starlink has offered low-cost connections. In Myanmar, Starlink terminals have enabled aid organizations and prodemocracy resistance groups to stay connected amid the devastating civil war, though the military regime’s forces have begun seizing terminals in response.

War journalist in a street filled with exploded tanks and destroyed buildings in the town of Bucha, northwest of the Ukrainian capital Kyiv. (Photo credit: Abaca Press via Alamy)

Because they are relatively new to the market, satellite-based internet service providers have not yet widely implemented the censorship and surveillance mechanisms required by many governments, particularly those in countries ranked Not Free in Freedom on the Net. As a result, some authorities have sought to ban them. The Cuban government banned the entry of unregistered satellite-linked devices into the country, seizing many in March 2025. In June 2025, after the coverage period, the Iranian parliament voted to ban Starlink altogether.

More commonly, governments have developed or enforced regulations to bring providers in line with local law, wielding the threat of bans or other penalties. These actions raise concerns about privacy and freedom of expression. The Cyberspace Administration of China, for example, issued a draft proposal in September 2024 that would require satellite internet providers to censor content in real time, maintaining the integrity of the Great Firewall even as Chinese satellite internet companies seek to compete with global peers in foreign markets. In December 2024, Kazakhstan’s government threatened to ban imports of satellite communications equipment before signing an agreement to allow Starlink to enter the market in June 2025, after this report’s coverage period. According to government officials, the company agreed to comply with Kazakhstan’s “information and communications” laws, which have historically enabled the authorities to restrict access to the internet and surveil users. In August 2025, after the coverage period, officials in India reported that Starlink had agreed to store local users’ data within the country in compliance with Indian law; the government had launched a probe into the unlawful use of the satellite service in January.

Internet connectivity in areas affected by armed conflict has been constrained by government pressure or by the risk calculations of service providers. As the two sides in Sudan’s civil war destroyed the country’s telecommunications infrastructure and imposed local service shutdowns, Sudanese people and aid groups turned to Starlink for emergency access to the internet. In April 2024, the company notified Sudanese users that it would limit services in the country due to regulatory constraints. Civil society organizations raised concerns about the impact of further connectivity restrictions on local humanitarian efforts, and Starlink ultimately appeared to remain accessible throughout the coverage period. Starlink has reportedly faced similar dilemmas in Russian-occupied Ukrainian territories and Israeli-occupied Palestinian territories, which are not covered by Freedom on the Net.

As the satellite internet market continues to grow, providers should prepare for further government pressure to carry out censorship and hand over user data. They should use all the resources at their disposal to reject or evade any disproportionate government demands that would violate users’ rights to free expression or privacy. These companies would also benefit from well-established mechanisms for multistakeholder collaboration on telecommunications services and human rights, like the Global Network Initiative, which can offer guidance on how to navigate state pressure.

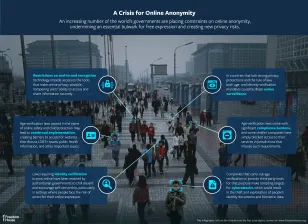

The end of online anonymity

An increasing number of the world’s governments are placing constraints on online anonymity. Some are limiting access to services that keep communications private. Others have mandated the use of identity verification technology as a condition for access to certain online spaces, including the most popular social media platforms. Online anonymity has long been a bulwark for free expression and access to information, empowering people to share their views online without fear of government retaliation, especially in closed societies where they could be unjustly persecuted for their political expression, their faith or nonbelief, or their identity. The restrictions on anonymity pose a direct threat to online privacy, free expression, and access to information, and could further carve up the global internet based on varying domestic rules for participation.

Though not without challenges, online anonymity has long been a bulwark for free expression and access to information, empowering people to share their views online without fear of government retaliation, especially in closed societies.

During this report’s coverage period, governments from across the democratic spectrum placed limits on tools that make online privacy possible. Throughout the summer of 2024, repressive governments in Myanmar, Russia, and Venezuela blocked the encrypted messaging platform Signal, which allows its users to share and access information free from surveillance. The United Kingdom’s government has sought to compel Apple to erode its end-to-end encryption standards, reportedly issuing demands to access encrypted data stored by Apple users in January 2025 and again in September 2025, after the coverage period. In February, the company limited UK-based users’ access to its Advanced Data Protection feature, which allows individuals to encrypt certain forms of iCloud data. People in 17 of the 72 countries covered by Freedom on the Net experienced blocks on end-to-end encrypted communications platforms between January 2020 and March 2025, according to recent Freedom House research published in partnership with the European University Institute.

Laws requiring identity verification to post online content present another avenue for undermining anonymity, and they have occasionally been enacted by authoritarian governments to curtail dissent. In Vietnam, a December 2024 law required users of social media platforms to authenticate their accounts with their government-issued identification documents or their Vietnamese mobile phone numbers, which are themselves subject to real-name registration. Real-name registration has been required to access internet services in China since at least 2012, and during the coverage period regulators experimented with a system that would centralize age-verification services for social media platforms through a government-controlled digital identity system. Belarusians posting content to local websites have been required to register their identities since 2019. These rules present a serious risk of harm, as people in all three countries—and many others—routinely face arrest and heavy criminal penalties for dissent expressed online.

Similar requirements in democracies are ushering in a new paradigm for access to information and online communication, as policymakers impose age-verification laws in the name of online safety and child protection. These laws may oblige users seeking certain content to upload a government identification card or submit to “age assurance” technology that employs facial analysis to estimate a person’s age. In November 2024, the Australian government passed a law that would ban children under 16 from accessing social media platforms, the most expansive measure of its kind; it is set to enter into force in December 2025. A March 2025 Indonesian regulation requires online platforms to implement age-verification features and enforce age restrictions based on whether they host pornographic or violent content, offer material with a potential for psychological harm, or have other “high-risk” features.

In some cases, these laws have led platforms to impose invasive age-verification measures for all their users, or to pull out of the market in question due to compliance burdens. Age-verification features of the United Kingdom’s Online Safety Act entered into force in July 2025, requiring users to provide government identification documents, facial scans, or credit cards to prove that they are not children; the rules apply to websites with broadly defined “harmful content,” leaving the websites themselves responsible for determining which content meets the definition. As they rolled out these features, there were notable examples of overbroad application, including for forums on LGBT+ issues, journalism, and public health. In the United States, a Mississippi state law that entered into force in August 2025, after the coverage period, required platforms to deploy age-verification systems to prevent children from creating accounts without parental consent. Several small platforms, like the social media application Bluesky and the blogging service Dreamwidth, have blocked access in Mississippi because of the compliance burden.

Other measures focus on pornography and sexual content. In the United States, a June 2025 Supreme Court decision affirmed that Texas could require age-verification features for “sexually explicit material,” finding that the state’s law “only incidentally burdens the protected speech of adults.” At least 24 US states had passed age-verification laws focused on such content by the end of the coverage period.

While protecting children online is an important and legitimate policy aim, measures that compel platforms to verify people’s identities introduce a range of new risks. In countries with weak rule of law and widespread government surveillance, age-verification laws are ripe for abuse. Even in countries with strong privacy laws in place, cybersecurity breaches at companies that carry out age verification or provide third-party tools could result in the leak of people’s identity documents or biometric data. The danger is more than hypothetical. In the 16 years since the launch and widespread adoption of India’s Aadhaar biometric identification system, breaches of third-party databases have resulted in leaks of hundreds of millions of Aadhaar numbers, fueling a black market for perpetrators of fraud and cybercrime. These companies are also a target for state-backed hackers. In August 2025, it was reported that a yearslong operation—dubbed Salt Typhoon—to infiltrate US telecommunications infrastructure had enabled a group of Chinese government-linked hackers to exfiltrate data pertaining to hundreds of millions of Americans.

Other measures are more effective at bridging child protection and fundamental rights. These include tailored regulation to require stronger default privacy settings for children on platforms that allow minors to create accounts, more stringent data protection standards for young people, and adequate resources for investigations into online child abuse. Platforms that allow children to create accounts also have an obligation to ensure that their services offer strong privacy and security safeguards by design. Meanwhile, promising efforts to develop privacy-preserving and rights-respecting methods for age verification are underway, and technologists, innovation-minded governments, and civil society groups should work together to encourage support and adoption.

Acting now for a freer future

Fifteen years of Freedom on the Net analysis has shown that innovation presents both opportunities for and challenges to human rights online. Social media platforms, initially heralded as drivers of political and economic liberation, have been exploited by autocratic regimes and other unscrupulous political forces to spew propaganda, censor protected expression, and surveil dissidents. The next wave of new technologies will transform how people exercise their rights in digital spaces.

AI is already becoming integrated into our daily lives, satellite internet service is expanding connectivity and competing with incumbent providers, and identity verification technology is reshaping access to online content and communities. By embedding safeguards for free expression and privacy into these systems at the earliest possible stage of development, democratic societies can ensure that they will fuel improvements for global internet freedom rather than contributing to another period of decline.

This report has been updated to correct the number of Free countries that saw score improvements over the coverage period. The correct figure is three countries, not two.

Test Your Knowledge

Test your knowledge of some of the key findings from our 2025 report by taking our quiz.

Report Resources

Report PDF

Download the complete Freedom on the Net 2025 PDF Booklet

Policy Recommendations

Learn how governments and companies can protect internet freedom.

Report Data

Interested in downloading Freedom on the Net report data? Please email [email protected] with "FOTN Data Request" in the subject line and our team will assist you.

Individual Country Reports

Visit our Countries in Detail page to view all of this year's scores and read abridged reports from each of the countries we cover.

Research Methodology

The Freedom on the Net index measures each country’s level of internet freedom based on a set of 21 questions.

Acknowledgements

The Freedom on the Net team expresses gratitude to the global internet freedom community, including the many individuals and organizations whose tireless and courageous work informs this report.

Sign up to receive the Freedom House weekly newsletter.